Right now I'm reading Mary Karr's The Liars Club (in a "10th anniversary edition" with a new forward by the author), and whether Karr is telling the truth or not, one thing is certain: she is a far better writer than the Million Pieces guy, who tends (among his merely stylistic faults) toward the Crude affectation of random Capitalization.

Not long ago I read another drunk's memoir, Dry, by gay New York adperson Augusten Burroughs. I didn't like it much. Despite what the reviews said ("fabulously funny"; "self-deprecatingly funny"; "funny and dark"), it just wasn't very funny. It's an odd description for a drunk memoir anyway (I say humorlessly), but if reviewers are describing you as funny, you should be funny.

A bigger problem

When Dry opens, Burroughs is only 24, but he's fabulously successful, he does glamorous things with glamorous people, and he lives in New York, the hippest city in the world. And he drinks. A lot.When Dry ends, Burroughs is only 25 or 26 (he's kind of vague about when and over how long a period his story takes place), he's still fabulously successful, and he still does glamorous things with glamorous people in New York, the hippest city in the world. But he doesn't drink. At all.

In between he has adventures, including rehab, and goes through many changes. Fine. Look, I'm sure he went through hell (and he apparently had a truly horrific childhood, which he recounts in a book called Running With Scissors), but to real, long-term drunks, Dry is lightweight stuff.

Certain things tend to happen to drunks. They:

None of these things happens to Burroughs (he doesn't even lose his job!), which, while wonderful for him, doesn't provide much excitement for the reader. (Burroughs does lose a friend, but to AIDS, not alcohol). Though I probably shouldn't put it this way, Burroughs is simply not a big enough or nasty enough drunk to sustain interest in his story.

AA people probably wouldn't like me saying this. For them, if you think you have a problem with alcohol, you do, or at least you should be treated as if you do. In the boozehound world, as opposed to some others, self-identification is perfectly acceptable. It just doesn't always make for gripping reading.

Nearly gratuitous Jack London quote!

And now comes John Barleycorn with the curse he lays upon the imaginative man who is lusty with life and desire to live. John Barleycorn sends his White Logic, the argent messenger of truth beyond truth, the antithesis of life, cruel and bleak as interstellar space, pulseless and frozen as absolute zero, dazzling with the frost of irrefragable logic and unforgettable fact. John Barleycorn will not let the dreamer dream, the liver live. He destroys birth and death, and dissipates to mist the paradox of being, until his victim cries out, as in "The City of Dreadful Night": "Our life's a cheat, our death a black abyss." And the feet of the victim of such dreadful intimacy take hold of the way of death--John Barleycorn: Alcoholic Memoirs (1913).

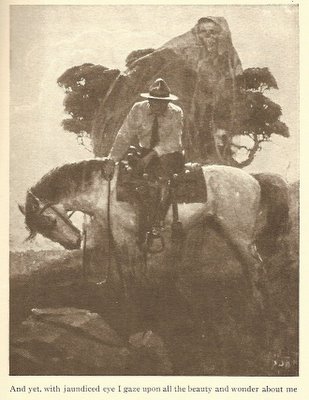

Illustration from the original edition of John Barleycorn.

Update: Linking to a band because they have a cool name or logo does not imply familiarity with that band's music.

No comments:

Post a Comment